“My board is driving me nuts!”

Today is “leap day” — that little something extra we’re given every four years, just to slow things down a bit and make February last a bit longer.

Leap day has something in common with nonprofit boards of directors — that little something extra, volunteers put in charge of the business, that has an unfortunate tendency to slow things down and make decision-making take a lot, lot longer than it usually should.

I recently came across a thoughtful article in the Huffington Post by Anne Wallestad, President and CEO, BoardSource, with the provocative title: Are Nonprofit Boards Really Necessary?

Perhaps doing away with boards entirely is too draconian a solution. Ann makes some valid points in support of their leadership, guidance and steadying hand in the face of a weak E.D. Yet, in practice, I’ve found that just as much instability can come from a dysfunctional board as from an errant E.D.

Could it be time for a new model of what a board should be and do?

Great boards are wonderful. And I generally find them in the same place I find a great E.D. It’s a match made in heaven. Other times, it’s like the blind leading the blind.

Particularly disturbing are the boards I run into with requirements they be comprised of a certain percentage of “community representatives.”

While this may sound lovely and egalitarian on paper, life is more three-dimensional. In practice, this often translates into board members who don’t give and don’t ask. In fact, these board members often bring a sense of entitlement to the table, rather than an attitude of giving and helping.

There’s also something a bit broken built into a model that has amateurs advising experts.

Here’s how this works. Boards are often comprised of folks who consider themselves “professionals” (in their day jobs they may be doctors, lawyers, architects, financial advisors, developers, business owners and so forth), but who know much less about the business of the nonprofit (including fundraising and marketing) than do the equally professional staff who work there, and who were hired for their particular expertise.

One of the main reasons there is so much turnover in the fundraising profession (and I suspect the E.D. position as well) is that staff don’t feel respected by their boards.

I worked for 30+ years as a development/marketing director, and I was excellent at my job. Yet new board members were constantly suggesting to me ways to do my job. For some reason they never considered that I might actually have already thought of these things — after having done this job successfully for quite some time. I know they were trying to help. Yet this required hours of my time — saying “thanks so much… great suggestion… let me think about this… let’s set up a time to talk about this…and so forth — all gently leading them to a place where they could understand why their idea didn’t really make sense (unless it did, in which case I was delighted to collaborate).

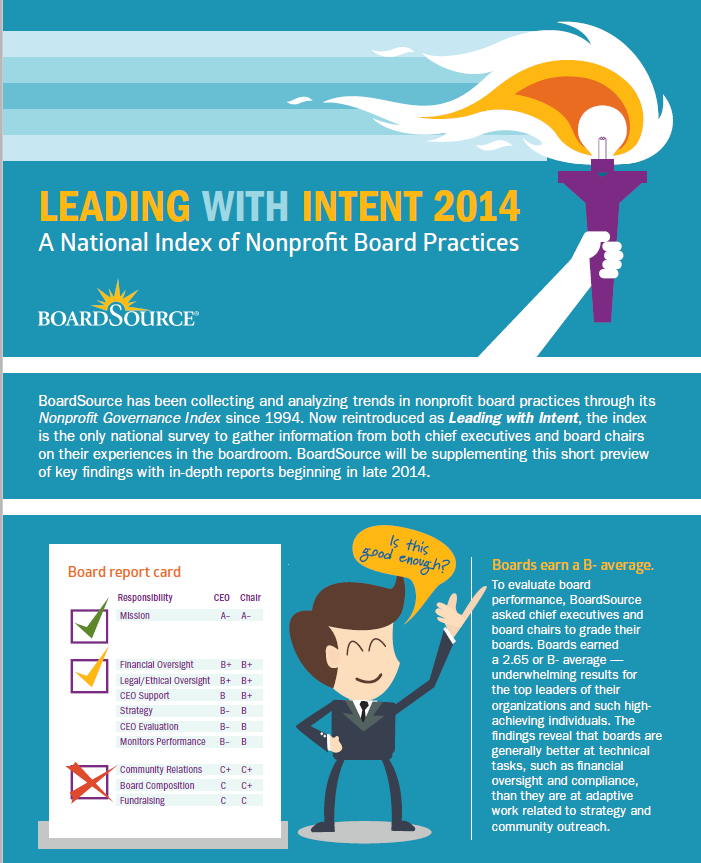

When asked by BoardSource, more than 1,000 nonprofit leaders gave nonprofits boards a “B-minus” grade in overall performance. Almost a third of nonprofit CEOs reported being unhappy with their boards’ support of them in their role as leader, and many of these folks were considering leaving their positions. When it comes to community relations and fundraising, CEOs rated their board members even worse — giving them a C! This is barely a passing grade.

There’s a problem when those in charge of setting the mission, policies, strategic plan and budget are doing a lousy job assuring that the resources are in place to fulfill this vision and assure that the decisions they make can actually be carried out. In government, we would call this an unfunded mandate.

Nonprofits get criticized for being slow to change.

Boards are one of the reasons why. Not only do they suck time from staff; they also slow down decision-making because everything has to be determined by consensus. You know what they say about trying to make decisions by committee? Everything can get watered down. There’s a tendency to cater to the lowest common denominator. And dangerous “group think” can set in, leading to emotion-driven decisions that can sometimes be quite extreme. Introducing new ideas can become a political mine field, and almost as challenging as trying to get a bill through today’s Congress.

Contributing to the problem is the fact that boards are naturally risk averse.

It’s their job, after all, to be good stewards of donor resources. Yet in our digitally revolutionized world, where change happens at the speed of light (or faster!), nonprofits have to take risks. They have to be nimble. They have to adapt. And they have to embrace failure. If they don’t fail, they don’t grow. And if they don’t grow, they die.

I’ve not run into may boards willing to embrace failure.

And why would they? This is just their volunteer job. They don’t want to be sued. It wouldn’t sit well, and it wouldn’t look good on their resume.

I’m not against boards. Not at all. I’ve had the privilege to work with some wonderful ones, and they were a great blessing. I’m just against dysfunctional boards. Ones that don’t respect their nonprofit staff. Ones that don’t lead.

In the nonprofit world, let’s face it, what the board does matters.

It matters a lot. Foundations and businesses will ask what the board is doing before they commit. Potential individual donors will decide how much to give based on the size of gifts committed by the board. New board members will decide whether they can abstain from fundraising based on the level of involvement in which they see existing board members engaged. And so on. We all naturally want to follow the leader.

Without a board that leads by positive example it will be extremely difficult for any social benefit organization to survive and thrive.

You see, it’s not what we say that really matters. It’s what we do. People won’t magically fall in line behind us just because we have a good case for support. Lots of organizations have a good case for support. People will line up behind a leader way before they’ll step up to the line on their own.

So how do we “fix” boards so they are more functional?

Is it time for a different model of board leadership? Does it mean we need some agreed-upon national standards of board composition, bylaws and job descriptions? How do E.D.s learn how to guide and support their boards? And vice-versa? Should board members be required to attend some sort of certification/training program? Should their E.D.s be encouraged to attend with them?

The very average level of board performance being reported by E.D.s currently should not be acceptable. We can do better. And to solve today’s most pressing problems, we must do better.

It’s going to take some kind of a LEAP of faith — so this might just be the year to do it.

What do you think can be done? Please leave your ideas in the comments section below.

Happy Leap Day.

Photos courtesy of imagerymajestic, Freedigitalphotos.com. Infographic courtesy of Board Source, Leading with Intent, a National Index of Nonprofit Board Practices

Want to get your staff and board on the same page? Consider working through the exercises in the 7 Clairification Keys to Unlock Your Nonprofit’s Fundraising Potential together. It will put the focus on issues, not personalities. And I guarantee you’ll learn a lot.