You’re in crisis.

You need contributions now, just to stay afloat.

Surely your donors understand and won’t mind if you tell them to just send money. Now!

While they may understand on some level, no one likes to be scolded.

Not even in a crisis situation.

Yet most nonprofits make a practice of regularly admonishing supporters to give “where most needed.”

You probably think this is a good thing. After all, it gives you the greatest flexibility. Right?

Wrong. Think again.

You’ll have a lot more flexibility, now and later, if you raise more money.

And you’ll raise a lot more money if you stop thinking about you and your needs and think more about your donors and their needs.

“The current economy is merely exacerbating a fundraising problem that has been around for a long time. On one side are Boards and CEOs insisting that they have to have the money now and that as much of it as possible must be raised unrestricted. On the other side are donors who have become increasingly frustrated with the organizations they support which either cannot or will not tell them, in measurable terms, how their gifts are being used. (“Lack of measurable results on their gifts at work” is the number one cause of donor attrition.) Caught in the middle are fundraisers who have not been very successful at getting their bosses to understand that only through restricted giving — i.e., by assigning gifts, whatever their value, to specific programs and services — can the evidence be generated that will satisfy donors and ensure their ongoing loyalty.”

— Penelope Burk, Burk’s Blog, Fundraising in Economic Turmoil – Your Donors’ Bottom Line. 12-08-2008

I’ll bet the date of that blog post surprised you! Because everything that’s said holds just as true today as it did in the 2008-09 recession. And every year thereafter. Have we learned nothing?

The practice of worshiping at the altar of unrestricted giving is about as non-donor-centered as it gets!

A prime example appeared a few years ago in an article I found on NPR (which has since been taken down from their site), in which the then CEO of National Philanthropic Trust chided potential donors to be loyal in their giving because it helps build planning. She said:

“It’s really expensive for charities to find new donors and to raise money, so by doing fewer larger gifts, and then staying with them for three to five years, you’re actually helping the charity plan better and it’s easier for them to meet their mission…. Really, if you like a charity and you’re going to give a small gift, consider giving an unrestricted gift. It really is the hardest money for them to raise … [and] charities that are well run will use it wisely, I promise you.”

She continued to warn donors not to make the “common mistake” of giving to a very specific project or narrow program within a charity. These “restricted gifts” she said, don’t help a charity out with its other needs such as computers, training and maintaining facilities.

Excuse me please, but… what hogwash!

It goes counter to intuition and common sense to force folks into your organization-centric mold.

Why not encourage supporters to give to those programs about which they’re most passionate? Wouldn’t you think that would bond them to your organization over the longer term in a more natural way than telling them the “healthy way” to give is akin to eating their vegetables?

I’ve never really understood the penchant in so many nonprofits to eschew restricted gifts.

Some do this to the extent that major gift officers are penalized for bringing in too few unrestricted gifts. Essentially, this means these fundraisers are not allowed to talk to donors about what the donor really cares about. Their task is to steer the donor away from their passions and towards a middle-of-the-road strategy that simply doesn’t excite them. This is absurd!

“It is more motivating for donors to sponsor something specific, for example providing supplies or a well for a school at a cost of $xx.”

— Anonymous donor, Burk Donor Survey

When you give people choices they’ll respond in greater numbers.

You see, if you package your overall case for support into different program ‘cases’ that resonate with people’s individual values, you’ll end up capturing more attention. People will actually read what you send to them. They’ll consider their options carefully. They’ll think about their giving. And they’ll make a thoughtful gift. Guess what else? A majority of folks will decide to give an unrestricted gift!

And those who decide to pick an individual program will still be supporting your general operations provided you package your overall case for support carefully. Feature your priority initiatives, the ones that combine to comprise the bulk of your work. It might be children, seniors and families. Or lions, tigers and bears. Or… (think of your top three, four or five key programs). Guess what? You’ll end up generating earmarked funds for your most popular programs. And you’ll likely raise more than you did before, because you’ve engaged people around their personal passions. What else? Now you know what floats people’s boats! You can report back to them on outcomes they most care about, and next year you can ask them for another gift to do something they really value.

But what if no one picks certain less popular programs?

Not a problem; you can direct your unrestricted funding there. You’re missing the boat if you simply talk in generalities and use unrestricted funds for the ‘sexy’ programs that could potentially bring in more donors and dollars. Yes, you need to keep the lights on. Yes, you appreciate donors who “get” this. Truly, I love the donors who give happily “where most needed.” But I also love those who give passionate, transformational gifts to a program near and dear to their heart. One is not better than the other. And there’s definitely room for both.

Wait, you say? What if we raise too much money for one program?

If that happens it’s not a bad problem. It should cause you to think. Whoa! People really like this program! Should we be doing more of it? Could we? Of course you don’t want unintentional mission drift, but thoughtful, strategic mission growth is a different thing.

Of course if you really end up with such an outpouring of support that you’ve more money than you can use, by all means, notify the donor and offer to return the money. This is not only the right thing to do; it’s also a good trust-building strategy. The fact you were able to generate so much community goodwill only reflects positively on you. And often the donor will tell you to keep the funds to use where most needed. Whatever happens, you’ve had an opportunity to deepen your relationship with this supporter.

But how do I put all these choices into an appeal?

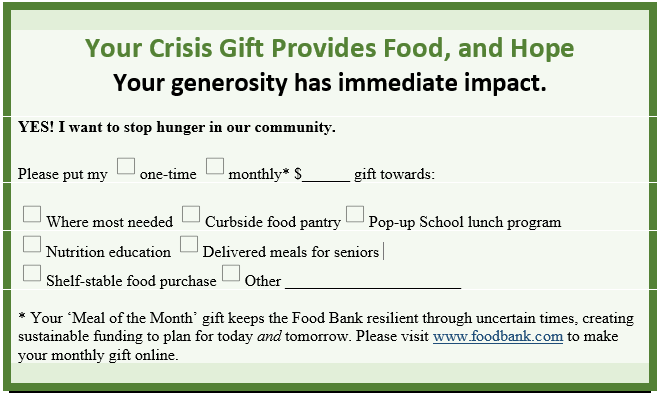

One option is to list choices on your remit envelope or donation landing page. Try something like this:

You can also ask for funds to support lions, tigers and bears in your appeal letter or email, and then note all gifts will support these and other critical needs. That way if you do exceed funding in one particular area of need you can legitimately fall back on your disclaimer of “other critical needs.” But I’d rather give check-off options as it gets donors more engaged.

Donors increasingly want to take an active role in how their money is spent.

This is a good thing. Greater engagement leads to greater loyalty and passion down the road. Younger generations, and major donors, are less inclined to let your organization decide how their philanthropy will be allocated. You’re competing in a landscape where other organizations are giving your potential donors the opportunity to be actively engaged in their giving.

If you don’t satisfy donors with enriching opportunities to provide specific solutions to specific problems, you will cease to be competitive in the donor marketplace.

Stop being afraid of offering restricted giving opportunities.

Think of it as a sales technique (and stop thinking sales is ‘yucky,’ when it’s profoundly human). Like going to a restaurant where you’re offered a bunch of a la carte options, and then the ‘Chef’s Choice.” After reading over all the enticing choices, a lot of people will happily choose the chef’s recommendation. And they’ll feel much better about this choice than they would have if that was all that was offered.

‘Take it or leave it’ is not particularly inviting. So offer supporters enticing giving opportunities that key into what they’re most passionate about. It doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll end up deciding to make a restricted gift. It does mean they’ll probably end up paying more attention to you and making a considered gift of some form.

In fact, a study of the world’s wealthiest donors found that even among the most affluent donors nearly 70% of those with $1 to $5 million in assets prefer to give unrestricted gifts to charity, while among those with assets of $50 million or more, 45% say they prefer to make unrestricted gifts. When you offer choices the upside is greater than the downside. For me, it’s a no-brainer.

What’s best for your donors is what’s best for you.

Generally, of course. I’m not suggesting you accept restricted gifts that cause mission drift any more than I’d suggest you order a chef to make you a dish that’s not on the menu. The point is that offering a menu helps everyone.

Being donor-centered means understanding what donors really want and need. The more you continue to approach donors from the perspective of what you need, the poorer results you’ll see.

It’s pretty much common sense, isn’t it?

Want More on This Topic?

Want More on This Topic?

How much more money could you raise if leadership began to think from your donor’s perspective rather than their own? A lot. That’s what I’m guessing. Grab my “Major Gifts Matters” FAQs about offering donors choices. If you don’t find it useful, I’ll happily refund your money — no questions asked!

I think you shouldn’t be scolding nonprofit donors in the first place. A donation is a donation, anything they give is without our control, as it is their right and free will to do so. What’s important is they are intending to help and give charity to those who are in need. Unless if they are just bullshitting around and not being serious with your cause, then that’s when you should step in, not scold but just talk them out of it.

Claire, I’ve been reading your blog for a long time, and this is the first time I’ve felt that you are really out of touch with what the goal of a non-profit is. I totally understand the donor-centric model, it helps make donors part of the organization and that helps the organization in the long run, but that may not help our clients out in the long-run. You complain about being organization-centric, but really, any non-profit organization should neither be donor-centric or organization-centric first, but client-centric.

I hear what you are saying about always giving the donor options–if they want to give towards something specific, we shouldn’t stop them, but by playing into these program models, we ultimately create organizations that do what makes donors happy, not what is best for the client or for the mission. It is also a question of changing the conversation–moving the conversation to General Operating Funds over time makes the culture of philanthropy different, and in general helps organizations better do their missions. Lately, in the conversations about race that have been talked about across the country, Vu Le talked about how non-profits may have become the white moderates that Dr. King warned would stop real change (https://nonprofitaf.com/2020/06/have-nonprofit-and-philanthropy-become-the-white-moderate-that-dr-king-warned-us-about/). Saying “What is best for your donors is what is best for you” is playing into that model. If non-profits take the donor first, then we recreate power structures that many times go against our larger mission.

Thanks for your thoughts Daniella. I’ve read Vu’s article, and also a more recent one where he writes: “Our communities cannot afford for us to doubt ourselves, be too deferential, or always default to philosophies and processes that we were trained in.” Ouch. I asked myself have I, as Vu suggests, been complicit in ‘furthering the injustice we are trying to fight?’ Vu exhorts us to transition to community-centric fundraising (which may be similar to your suggestion of client-centrism, yet perhaps more encompassing). I don’t disagree. I’ve long looked to Darwin and his theory of ‘survival of the most empathic,’ believing the communities who care for their members are the ones that survive. I still believe there’s an elegant solution (breaking apart core expenses into more enticing ‘packages’) to making donors happy and still raising the funds you need to help the many who rely on you. I’m hoping there’s a way to ‘ask not what your donors can do for you, but what you can do for your donors’ and still adhere to what both of you, together, can best do for the community. I’m not sure what this will look like. But I know there’s a thirst among many to see, and be, a part of pushing back against oppression and exploring better ways of doing business. Thank you for being one of these people.

Yes. Yes, and Yes. I regularly have this conversation with clients who are holding so tightly to unrestricted gifts that they are strangling themselves. Thank you!

Thanks Diane for doing your important work, and trying to help nonprofits not leave money on the table.