Just like it’s prudent for individuals to have both a checking and savings account, it’s prudent for nonprofits to have both operating funds and endowment reserves.

Just like it’s prudent for individuals to have both a checking and savings account, it’s prudent for nonprofits to have both operating funds and endowment reserves.

Living paycheck to paycheck is less than ideal, especially when constituents rely on you for services that really matter. Seriously ask yourself:

- Are we potentially one lost grant away from having to close our doors? Funders change priorities all the time.

- Would losing one major donor gift mean we might not make payroll? People move. People die. People change their loyalties and areas of interest.

- If we don’t do a big special event every year, will we need to cut programs? This happened to many nonprofits during the pandemic.

- Am I regularly losing sleep over not being able to pay rent? Without insurance against funding cutbacks, your focus is always on survival rather than effective planning and management.

If your answer to any of these questions is affirmative, you’re living on quicksand. When you’re not actively safeguarding your future, you’re robbing your community of precious resources.

Does this sound like a prudent, caring way for your nonprofit to behave?

Not if you see yourself as a community.

A Community Cares for its Members

Without caring, you’re just a zip code or a building, not a community.

Make this the year you demonstrate your caring by planting seeds for future harvests.

You can’t care for people, animals, places, things or values without nourishment and fuel. As a recipient of philanthropy, it’s your job to steward the resources others give so you’ll be there for the community when they need you most.

- If you don’t plan ahead to survive and thrive…

- If you don’t plan for growth that may be necessary as new needs arise…

- If you allow vital resources to run out…

You fail.

Your community fails too.

NOTE: While known for the theory of “survival of the fittest” (which actually was coined by the philosopher Herbert Spencer), Charles Darwin posited the notion of “survival of the kindest,” finding sympathy to be the strongest human instinct. You see, survival doesn’t necessarily mean the strongest or most aggressive person. It depends, as much if not more, on cooperation and empathy between and among people. And the communities where people cared for one another endured.

How to Care for Your Community’s Future

Any nonprofit that’s been around for ten years or more needs to build an endowment. Why? Because with that type of longevity it’s likely people have come to count on you. They would miss you if you were gone.

Because you’ve been successful, you’ve earned the privilege – and responsibility – to fundraise.

How big does your responsible endowment need to be? There’s no one right answer. In my 30 years of fundraising in the trenches, I learned it should be at minimum two times the size of your operating budget. It’s a benchmark I found useful sharing with boards. But if that seems daunting, there are other ways to sell your board and/or donors on the need for an adequate cash-reserve fund before starting an endowment.

Really, you need a corpus large enough that the income it throws off annually could see you through an emergency. In other words, could it replace the income from a grant, major gift or event revenue that was cut off in a given year? Would it be enough to respond to an increase in demand of 10, 25 or even 50 percent? Would it help you and others sleep peacefully at night?

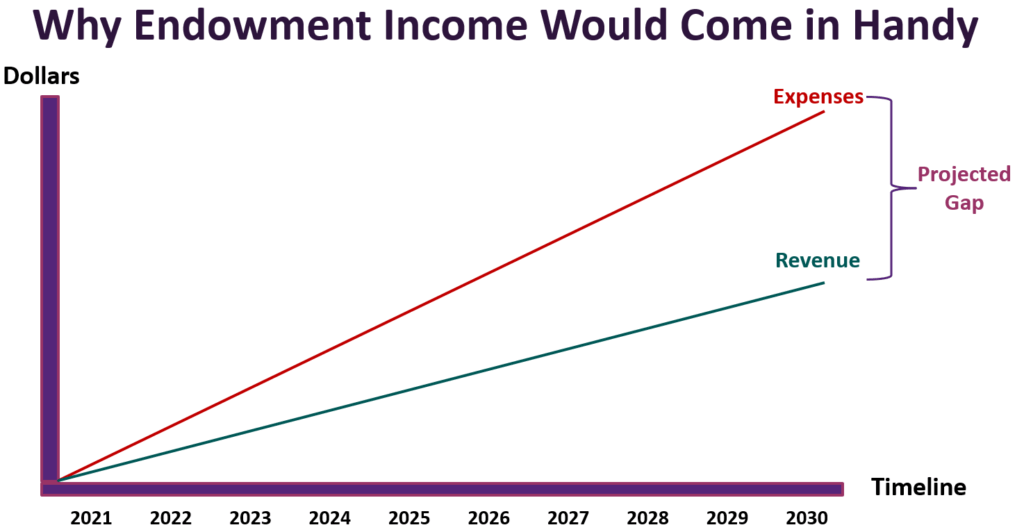

TIP: I recommend creating a spreadsheet, and accompanying graph, projecting an increase in expenses over the next ten years. Also project the increase/decrease in revenues. Most often, nonprofits will find a sizeable gap between the two, with expenses coming out on top. The amount of this income gap is the amount your endowment corpus will need to earn in order to fill the gap.

Make a Concrete Case for Endowment

Show your graph – and projected annual fundraising shortfall – to your ‘powers that be.’ This is a fact-based, visually compelling way to begin a conversation about why it is responsible to build an endowment through legacy giving (sometimes called “planned giving.”)

Part of your job is to dispel the myth that, somehow, having any cash reserves is immoral for a nonprofit. Responsible business owners – including your board members and donors – 100% understand the need to keep some cash in reserve. Just because you’re a mission-focused rather than a profit-focused business does not mean it’s any different for you.

Board members have a fiduciary responsibility to assure you have sufficient financial resources to fulfill your mission both today and for the future. Planning for survival is smart. Period.

Draft Your Legacy Giving Program Blueprint

Once you’ve made your case for support, it’s time to craft a manageable plan to generate that support. Don’t put this off until you feel “established” enough to begin to build a savings account. Again, if you’ve been around for ten years or more, it’s not too early.

The process need not be complex. Sure, you’ll flesh it out over the years and add in bells and whistles. But don’t get distracted by the shiny stuff at the outset. You can accomplish a lot with just four simple steps.

4 Legacy Giving Program Building Blocks

Has it been one of your new year’s resolutions – for more years than one — to ramp up your legacy giving program? This year, commit to crafting your case for support, as described above. Then, really, really, really do these four things! Seriously, I consider it fundraising malpractice not to.

Today I’ll share Step #1. Next week I’ll share Steps #2, 3 and 4.

1. Identify top prospects.

First talk to those most closely identified with and connected to your cause. These are the people with whom your case for support will most readily resonate. They love you, and wouldn’t want to see your work compromised or, even worse, extinguished.

Rather than worrying at the outset about communicating with the masses, or putting up planned giving landing pages you’ll hope folks will find on their own, worry about reaching out directly to folks you know how to reach. Folks who will take your call. You can always put information on your website later, and share legacy giving opportunities more broadly, but that shouldn’t be your priority focus. In fact, that’s a recipe for keeping donors at arm’s length.

Get up close and personal; I recommend beginning with your board and current loyal donors. These people don’t have to be rich, just devoted. You’d be amazed how many teachers, nurses and postal workers have left $1+ million legacies. Talk with these connected prospects one-to-one or in small groups. Make the case. Ask them:

- How do you feel about our organization building endowment?

- What about it do you think is important?

- What reservations, if any, do you have?

- Do you have any feedback about how to build one?

- Have you personally made a provision for our organization in your estate plans?

- If so, how? If not, why not?

- What would it take for you to consider a legacy gift?

- Can we publicly share your testimonial to inspire others to follow suit?

- Would you be willing to talk to others about leaving a legacy?

This methodology yields amazing results. I have personally reached out in this way with multiple organizations, always resulting in a positive outcome. In one organization, a full 50% of those I spoke with ended up making a bequest, beneficiary designation or some other type of planned legacy gift! As surprising as this may seem, the bottom line is these donors simply hadn’t considered it before (no surprise really, because being asked is the primary reason people give), and didn’t realize it could be so easy (which it truly can, if you stick with the basics – more on that next week) or so fulfilling.

Stay tuned for the next article in this two-part series: 4 Legacy Giving Program Building Blocks

Image — Three-San-Francisco-Hearts: Hope-BLooms-Connected-Poppies-by-the-Bay. Benefit for S.F. General Hospital Foundation