Fundamentals are important! Before writing your appeal, it’s good to remind yourself of the basics to make sure you’ve got all bases covered. Look at the elements you want to include; make sure you’re applying them. In this two-part series, I’m calling out eight appeal writing fundamentals. In Part 1 we looked at the first four:

Fundamentals are important! Before writing your appeal, it’s good to remind yourself of the basics to make sure you’ve got all bases covered. Look at the elements you want to include; make sure you’re applying them. In this two-part series, I’m calling out eight appeal writing fundamentals. In Part 1 we looked at the first four:

-

- You

- Easy

- Welcome

- Heart-awakening

Today we continue with four more.

-

- Best Self

- Uplift

- Unconditional Love

- Urgency

Let’s get started!

5. BEST SELF

What if part of the reason our sector has so little understanding of our supporters is because we think we’ve done the work of understanding by slapping the activist, volunteer, donor (insert other generic label here) on people?

— Kevin Shulman, Founder, DonorVoice

Donors have their own sense of identity; they’re people first. Trying to categorize them neatly into donor “personas” (e.g., “Wanda Widow,” “Busby Business Man,” “Suzy Soccer Mom,)” doesn’t work nearly as well as helping them express their best self or selves. A self with which they most closely identify.

Even if readers haven’t directly experienced the problem your charity seeks to resolve, your letter can speak to something important in the donor’s identity. Your goal is to speak to the part of this person that can identify and empathize.

- Any parent can imagine what it would be like to have a terminally ill child. Speak to the parent.

- Any friend or family member can imagine what it would be like to lose a loved one. Speak to the friend or family member.

- Any lover of the wild can imagine what it would be like to no longer be able to enjoy a favorite river due to pollution. Speak to the river lover.

- Any arts and culture lover can imagine what it would be like if their favorite theater, dance company, public radio station or museum shut down. Speak to the arts and culture lover.

One way to do this is to use words and images that connect the reader to beneficiaries of your work. If it’s troubled children, maybe they see a troubled child in their own past or, potentially, in their own child’s future. If it’s students who received scholarships, maybe they were a scholarship beneficiary and can be inspired to give back. If it’s job mentoring services, maybe it will remind them of the importance of a mentor in their own life and inspire them to pay it forward.

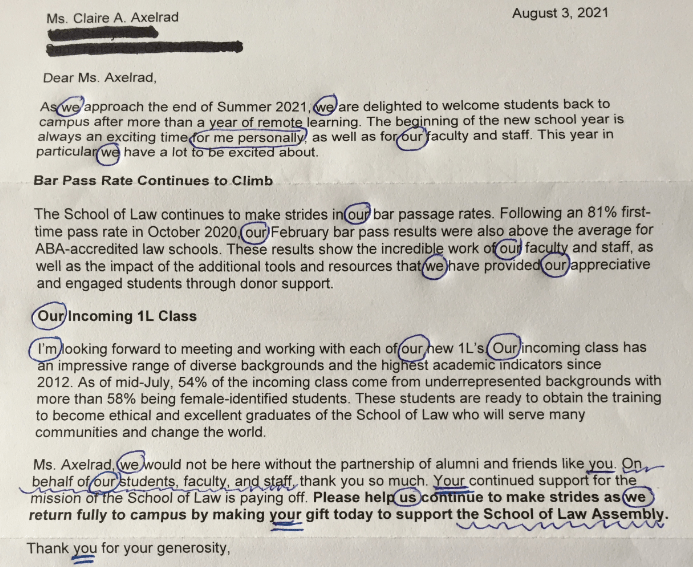

In Part 1 I shared a letter sent from a Law School to its alumni as an example of appeal writing gone awry. Here it is again, with my annotations, in case you didn’t read the last article.

By now you can probably guess how the Law School Letter example does on the “best self” test:

- The only identity it speaks to is assumed to be mine as an alum of this school. (Whatever they may believe, it’s not an important part of my identity; I ceased actively practicing law decades ago and didn’t really enjoy my graduate school experience).

- What they could have discovered if they’d bothered to ask (e.g., via survey) was I do actively support charities providing legal aid, access to equal rights and due process. In fact, I’m over the moon about the important role the legal justice system plays in our society right now; they failed to connect with this part of my self-identity.

6. UPLIFT

Our premise is that defining people by their aspirations and contributions is essential before acknowledging their challenges and investing in them for their continued benefit to society.

— Trabian Shorters, founder of BMe Community, Chronicle of Philanthropy

Giving should lift people up, not drag them down. This is why I’ve long counseled fundraisers approaching donors to retire phrases like “Let’s go hit them up” or “I’m going to twist their arm” for a gift. Yipes!

The same holds true when considering how we talk about philanthropic beneficiaries. It’s incumbent on fundraisers not to drag any people down by the language they habitually use. Often without thinking, appeals become filled with words that define people as at-risk, absent, marginalized, disaffected and in need of rescue. Yet there’s research showing we lift both our beneficiaries and donors up when we use aspirational language.

When it comes to beneficiaries, we can either prime people to fix the system or stigmatize the aspiring beneficiary. .Again the research from Daniel Kahneman shows how wrong the nonprofit world’s practice of stigmatizing charitable recipients is. How we frame things matters, and “A black student striving to overcome a threatening environment and graduate” is a more accurate description than slapping on an “at-risk youth” or “homeless youth” label. In the first framing, we acknowledge the youth is a student whose hopes are threatened by the system in which they live. In the latter, we vilify the beneficiary in a way that makes it too easy to blame them for their plight. Focusing on talents beats focusing on tribulations. It makes donors want to nurture the good.

When it comes to donors, people’s giving must promote their not just their best selves but also their personal wellbeing. According to Drs. Adrien Sargeant and Jen Shang, who run a course on philanthropic psychology, there are three aspects to this:

(1) Connection: Relationship building is at the core of successful philanthropy facilitation. There’s so much research showing the deleterious effects of isolation and loneliness on health and wellbeing, I’ve often wondered why social benefit organizations don’t see uplifting volunteers and donors as absolutely central to their missions. Certainly the more you can build these human connections the more you’ll meet donor needs. When you help others, they help you.

(2) Competence: Feeling capable is a core human need. When we feel the world is out of control, we seek to control what we can. It’s often hard to do this on our own, but much can be accomplished working with, and through, others. Charities can offer donors an opportunity to feel good about how they love others through philanthropy.

(3) Autonomy: Beyond feeling competent as philanthropists, donors must feel a sense of autonomy. They must own their choices, rather than feeling they’re just following orders. This is why I recommend offering choices for how gifts may be earmarked. There are ways to identify core initiatives within your operating budget, wrap them up into distinct packages, and then ask donors to pick the ones they find most resonant. When people feel they have a say in something, or a hand in making something good happen, they experience greater levels of wellbeing. So giving donors a voice and agency in the impact they have is crucial.

Let’s review the Law School Letter again to see if it is at all uplifting:

- The only attempt to connect the reader is to call them “alumni and friends.” It’s not even segmented between the two distinct groups. (I have no feeling they know who I am, or even care to get to know me. They don’t even call me by my first name!).

- There’s no attempt to re-inforce any feelings of competence I may have. In fact, quite the opposite. They tell me my “continued support” is paying off. (I can’t remember the last time I made a donation, but it was a long time ago. So… should I feel guilty?).

- They offer no opportunity for me to take autonomous control of my giving. I’m asked to support the School of Law Assembly (I have no idea what that accomplishes).

7. UNCONDITIONAL LOVE

I began to understand that philanthropy is a way for people to experience human love.

— Dr. Jen Shang, Co-Founder, Institute for Sustainable Philanthropy

Does a culture of philanthropy – love of humanity – shine through in your writing? It will if you can make the reader feel great about themselves, whether they give or not at this particular point in time. This tends to happen only in cultures where this type of love is the air everyone breathes.

Dr. Shang believes “Really good fundraisers already understand that people who give to charity have higher moral ideals, experience love more and are happier – but because the experiments are not being carried out, this has not been supported by evidence. If we could prove this, it would make fundraisers feel better about their jobs.” In the six years since she made this statement, much research has shown the benefits of coming at fundraising from a place of love.

Letters that sprinkle a healthy amount of gratitude throughout do this effectively.

- Thank the donor for past support

- Thank the volunteer for time.

- Thank the board member for vision.

- Thank the community member for leadership.

- Thank others on your mailing list for caring.

Whatever you do, assume the best of intentions and values among your readership. Not just in your thank you letters, but in your appeal letters too! Gratitude makes people happier. When people read and see themselves as the good people you appear to think they are, they’re more likely to act accordingly. Robert Cialdini, author of Influence, the Psychology of Persuasion, found people are wired to be consistent; they want to match the view you have of them being positively committed.

The Law School Letter example doesn’t focus on love or fulfilling on demonstrated commitment.

- The gratitude is inauthentic. I’m thanked in the final paragraph for things I know I haven’t done. (That doesn’t feel genuine).

- The first time it talks about changing the world is in the third paragraph, where it talks about the possibility the incoming students will do this. (There’s no mention of anything good I may have done, or why I might be loved as a result).

8. URGENCY

Urgency is one of the most important features of strong fundraising. That’s because for most donors, deciding they’ll give later is a default decision not to give ever.

— Jeff Brooks, Future Fundraising Now

Your donor needs a reason to give NOW, and to give to YOU rather than someone else. Put your appeal into a current context. What’s happening in the world that’s top of mind for your donors? Sprinkle the sense of urgency throughout your letter. Don’t wait until your final call to action to say “Please give today.” The “why” should begin your appeal, and then permeate all through your writing.

Inertia is the enemy of fundraising. You want to strike while the iron is hot! If your appeal has done an excellent job awakening the donor’s heart, and making them feel giving to you aligns with their values, have you also given them a reason to do this right now? You better, because “cool down” happens fast.

Emotional giving is impulsive. When something appears urgently needed, people don’t deliberate. They think fast, not slow; emotionally, not rationally (this happens to be the premise of Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, a book I highly recommend). Help donors act on their impulse by offering a deadline or other rationale for giving immediately.

- The match ends at midnight tonight.

- People are on the streets right now.

- Disaster victims need help right away.

- Without your gift this week, the doors will close.

- Overnight, demand for food has doubled.

- The weather forecast for next week is blistering cold.

Again, the Law School Letter example has no urgency:

- The only timely element is a mention students are coming fully back to campus. But there’s no mention of how this might relate to the timing of my gift.

- If they had said “We need to put safety measures in place right away, before students return!” that might have had some immediate resonance. They didn’t.

A good annual fundraising appeal is not a monologue testifying to your greatness.

Keep your donor’s perspective at the forefront of your writing. As you read through your appeal draft, consider:

- Who the reader is.

- What the reader cares about.

- What the reader knows/doesn’t know about what you do.

- What the reader has done – the love and commitment they’ve demonstrated – in the past.

- What might move the reader to positively answer your call to action.

- What might make the reader feel really good, whether they act now or not.

- How might you follow up next with the reader, whether they give now or not.

Want to learn more about effective fundraising appeal writing?

Grab my Anatomy of a Fundraising Appeal + Sample Template. This is a simple, yet incredibly thorough, 62-page step-by-step guide to crafting a killer appeal letter or email appeal. It’s not just a breezy 2-page form, like what you’ll find elsewhere. Because writing a compelling fundraising letter can be tricky. It’s not the same kind of writing as a brochure, annual report or grant proposal. But it’s not rocket science – it’s something you can easily learn. It’s just not something most of us are taught. And that’s where this nifty e-Guide comes in!

Grab my Anatomy of a Fundraising Appeal + Sample Template. This is a simple, yet incredibly thorough, 62-page step-by-step guide to crafting a killer appeal letter or email appeal. It’s not just a breezy 2-page form, like what you’ll find elsewhere. Because writing a compelling fundraising letter can be tricky. It’s not the same kind of writing as a brochure, annual report or grant proposal. But it’s not rocket science – it’s something you can easily learn. It’s just not something most of us are taught. And that’s where this nifty e-Guide comes in!

Not satisfied for any reason? No worries. You have my no-questions-asked, 30-day, 100% refund guarantee. Now… onward and upward to fundraising appeal success!

Note: My intention is never to shame any charity, merely to point out examples – Do’s and Don’ts – to help the broader social benefit sector. If you happen to work for the organization that wrote this letter, and would like a personal coaching session, please don’t hesitate to reach out. Maybe you’ll tell me it raised a ton of money, which I would be happy (albeit curious) to hear. Fundraising, like anything else worth doing, is a process of continuous learning. Thank you.

Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

I have found this article helpful. Thanks for sharing.