Beware the “drop in the bucket” effect.

There’s a powerful psychological principle known as the “identifiable victim effect.”

It has to do with how you describe the scope of the problem you’re asking donors to help address. And what they will do as a result of how they perceive this scope.

- Is it a scope they can visualize and relate to?

- Or is the number so large it’s difficult for them to wrap their brains around it?

There’s another related psychological principle known as “scope insensitivity.”

It applies when a number is too large for people to really comprehend its meaning. If you tell me something costs $1 billion, I really have little idea how this might differ from $10 million. Both numbers are equally overwhelming. I can’t picture how high a pile of either would be in dollar bills or even $100 bills. I have no sensitivity as to the scope because I simple can’t sense it.

Fundraisers absolutely need to know about, and apply, these principles.

Identifiable Victims Evoke Sympathy, Triggering Generosity

“If only one man dies of hunger, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.”

– Lenin

Numerous cases point to the manner in which a single, compellingly told story can move people to give with great compassion and generosity.

- In 1987, one child, ‘‘Baby Jessica,’’ received over $700,000 in public donations when she fell in a well near her home in Texas.

- More than $48,000 was contributed to save Forgea, a stranded dog on a ship adrift on the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii.

- In 2003 a wounded Iraqi boy, “Orphan Ali,” captivated European news media during the Iraq conflict and £275,000 was quickly raised for his medical care.

Researchers found people approach a single story with the emotional part of their brain; statistics cause them to reason with a different processing part of their brain.

When people are processing deliberatively, they are less sympathetic; more callous.

In Sympathy and callousness: The impact of deliberative thought Deborah A. Small, George Loewenstein, and Paul Slovic examined the impact of deliberating about donation decisions on generosity. People concentrated more money on a single victim, even when greater numbers would be helped if resources were dispersed more widely. Once people were made aware of the discrepancy in giving toward identifiable vs. statistical victims, their reasoning kicked in. This had a perverse effect, causing people to give less to identifiable victims but to not increase giving to statistical victims, resulting in an overall reduction in caring and philanthropy.

When thinking deliberatively, people discount sympathy towards identifiable victims but fail to generate sympathy toward statistical victims.

HEART OVER HEAD. EVERY TIME.

How You Describe Scope has a Big Impact

‘‘If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.’’

— Mother Teresa

There have been numerous field experiments demonstrating how people do not value lives consistently.

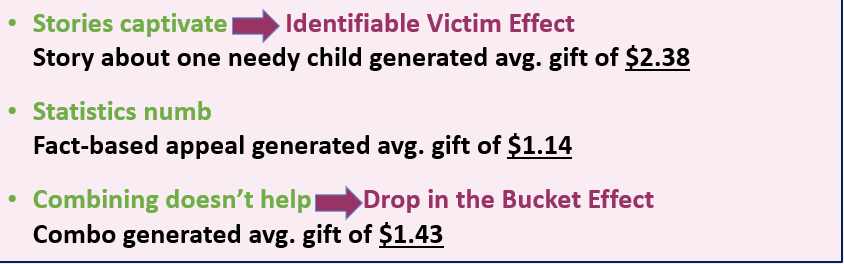

I’ll delve into some of this research later, but let’s cut right to the chase with the most famous experiment in the field – the one that gave us two important concepts:

- Identifiable victim effect

- Drop in the bucket effect

Paul Slovic and his colleagues found in a 2007 experiment with Save the Children that those who received a fact-based appeal donated $1.14. Those who read a story about an individual child in need donated an average of $2.38, more than twice as much. Combining the story with the numbers reduced the average contribution down to $1.43.

Why this result?

Data is hard to grasp. The average person doesn’t care about concentration of E. coli in an aquifer, but will do everything in their power to keep poop out of their tap water.

Combining data with narrative helps a little, but the numbers still lead people to discount the problem’s scope. Researchers called this the “drop in the bucket effect.” People were moved by the individual child’s story. When they read the numbers, however, they felt overwhelmed by the scope of problem. It felt like peeing in the ocean to raise the level of the sea. So they gave less.

NARRATIVE BEATS NUMBERS. EVERY TIME.

People Respond to Numbers They Can Grasp

“Altruistic motivation, such as willingness to contribute to help a victim, is directly related to aroused empathic emotion.”

Emotion is not aroused by huge numbers.

In one experiment three groups of subjects were asked how much they would pay to save 2000 / 20,000 / 200,000 migrating birds from drowning in uncovered oil ponds. The groups respectively answered $80, $78, and $88. The number of birds saved – the scope of the altruistic action – had relatively little effect on willingness to pay. What did arouse an emotional response was the single prototype — 1 exhausted bird… feathers soaked in black oil… unable to escape.

Seth Godin says when a donor is presented with an offer that involves making a decision of scale, if the number is greater than 10 the scope of the problem will be underestimated. Since no human can visualize 2,000 birds at once, let alone 20,000 or 200,000, data at best just reinforces their emotional decision. Scope gets tossed out the window.

THE BIGGER THE PROBLEM, THE LESS RELATABLE. EVERY TIME.

Relative Numbers Matter

If you send an appeal asking your donor to help 10 people evicted from their homes due to a fire, and there are only 200 people in the community, this will evoke great concern. Ten deaths out of 200 is a large proportion. However, people exhibit much less concern if that same fire causes 10 deaths throughout a population of many million people. Ten deaths out of many million is merely a ‘‘drop in the bucket.’’

Researchers call this the ‘‘proportion of the reference group effect.’’

People have difficulty evaluating the goodness of saving a stated number of lives, since an absolute number of lives does not map easily to an implicit scale Proportions of lives are, at least superficially, easy to interpret since the scale ranges from 0 to 100%.

A high proportion elicits stronger support for life-saving interventions, even when the absolute number of lives saved is small. In contrast, interventions that save larger numbers of absolute lives but smaller numbers of relative lives are likely to evoke weaker support. This sensitivity to relative savings even when absolute savings are reduced has been termed proportion dominance.

PEOPLE CARE MORE ABOUT 10 OUT OF 10 THAN 10 OUT OF 1,000. EVERY TIME.

Known Individual Targets Stimulate More Powerful Response than Unknown and Group Targets

Victims don’t necessarily have to be “identified” in the manner of Baby Jessica, Orphan Ali or Forgea the dog. An experiment examining donations to Habitat for Humanity to build a house for a needy family informed supporters either that the family ‘‘has been selected’’ or ‘‘will be selected.’’ In neither condition were respondents told which family had been or would be selected.

Contributions were significantly greater when the family had already been determined.

Another study found a single, identified victim (identified by a name and face) elicited greater emotional distress and more donations than a group of identified victims and more than both a single and group of unidentified victims.

EMOTIONAL REACTION TO A KNOWN, IDENTIFIED VICTIM IS A MAJOR TRIGGER OF SYMPATHY. EVERY TIME.

Thinking Fast Results in Greater Giving than Thinking Slow

“System 1″ is fast, instinctive and emotional; “System 2” is slower, more deliberative, and more logical.”

– Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky

The negative impact of deliberative thought, which comes into play when large numbers and data are introduced into fundraising and marketing materials, is discussed above. But there’s more.

Deliberative thinking (triggered by data) takes us away from our emotions (triggered by stories).

Beginning as early as 1980, Richard Nisbett and two fellow psychologists conducted a study to see if a single, vivid story (i.e., a very small sample) would more powerfully affect test subjects than authoritative data on the same topic. In fact, it did. When subjects were told a story it caused them to think very differently and had an enormous impact on their reasoning. People, the researchers concluded, use two basic sorts of cognitive tools to solve inferential problems-” ‘knowledge structures’ which allow the individual to define and interpret the data of physical and social life and ‘judgmental heuristics’ which reduce complex inferential tasks to simple judgmental operations.”

The simpler you can make it for your donor to think about arriving at a yes/no decision, the better.

Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky spent over two decades conducting their own experiments, and reported their conclusions in their now well-known book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow.” When we think slow it’s often because we’ve been presented with statistics, which we have a really hard time processing. It turns out the affective (judgmental) system is a faster, more automatic system whose output occurs before the output of the deliberative system, which involves slower, more effortful processing.

Depending on whether your prospective donor is using affective thought or deliberative, calculative reasoning, their response to your appeal will likely differ.

Whenever you add statistics to your appeal your donor will slow down to further deliberate and consider your ask. This tends to work to your detriment, as the act of thinking and interpreting will water down any emotional stimuli that have been triggered. Your donor may now put your appeal aside for later, rather than responding immediately. Often, that will be the end of it, because their emotions will no longer be powerfully aroused.

YOU WANT TO STRIKE WHILE THE IRON IS HOT. EVERY TIME.

4 Fundraising & Nonprofit Marketing ‘Scope’ Take-Aways:

- Show a compelling relevant problem the donor can grasp. EVERY TIME.

Embrace the “identifiable victim” effect. People will more likely give when they can connect emotionally and feel sympathy or empathy towards potential beneficiaries of their philanthropy. Since humans are wired to enter into stories, it just makes sense to present the problem you want help with in the form of a compelling story.

- Show impact on a scale your donor can visualize. EVERY TIME.

Beware the “drop in the bucket” effect. Donors want to make a significant impact. Don’t use numbers larger than 10 if you can avoid it. And try to break down your appeal into outcomes your donor can make possible at different levels of giving – e.g., $100 pays for four hours of home care; $250 pays for 10 hours of home care; $1,000 pays for one week of home care. When donors can visualize the scale of the outcome, they’ll be likelier to believe they can make a real difference.

- Avoid weighing down your communications with data. EVERY TIME.

Sympathetic reactions are undermined by deliberative thinking. Statistics cause people to weigh the scope of problems and deliberate about alternative uses for their money. As they slow down, their impulse to help might be diminished.

- Identify who will benefit. EVERY TIME.

Identifiable victims invoke the affective system by intensifying feelings. When folks read your appeal or thank you, you want them to feel rather than think. Even after donors give, sharing specific success stories (including visuals) with them will set them up to want to give their next gift.

Want to Learn More about Making your Appeal the Best it Can Be?

This 62-page guide will take your appeal letter from run of the mill to out of the ballpark!

Grab Anatomy of a Fundraising Appeal Letter + Sample Template. Writing a compelling fundraising letter can be tricky. But it’s not rocket science – it’s something you can easily learn. It’s just not something most of us are taught. And that’s where this nifty e-Guide comes in!

How much more money could you raise with your appeal letter if it spoke straight to the heart – and to your donor’s passions? I’m betting a lot. A lot more than the cost of this e-Guide, so what do you have to lose? (Plus all Clairification products come with a 30-day 100% refund policy, no questions asked.

If you’re ignoring any of the elements that go into making your appeal effective you’re ignoring your organization’s future. Let me help you!