The inimitable Seth Godin recently posted some wisdom I want to share, because it applies directly to how you must ‘sell’ your nonprofit if you hope to inspire folks to join with you to solve the problems you address.

The inimitable Seth Godin recently posted some wisdom I want to share, because it applies directly to how you must ‘sell’ your nonprofit if you hope to inspire folks to join with you to solve the problems you address.

As is always the case with Godin, it is succinct. It’s also both common-sense and deeply insightful — critically so — when you take a moment to dig in a little. It relates to one of the most critical elements of any fundraising appeal:

The problem.

You see, folks won’t give to you simply because you exist. Or because you’re nonprofit. Or because you’re ‘do-gooders.’

They won’t even give to you because you claim you’re addressing important issues or resolving a significant problem.

It takes more than that to capture people’s imaginations and inspire philanthropy.

The problem has to be vital, and the solving of it relevant, to them.

There are at least nine different ways in which a problem will capture a donor’s attention.

Here’s what Seth Godin has to say:

Some problems are easier to sell

In order to solve a problem, you need to sell it first. To get it on the radar, and to have people devote time, resources and behavior change to address it.

Human beings in our culture are wired to pay attention to problems that are:

Visible–right in front of our eyes, not microscopic or far away.

Non-chronic–rationalization is our specialty, and the reason we learn to rationalize is so that we don’t go insane when faced with long-term, persistent issues. We bargain them down the priority list.

Symptomatic–this is a version of ‘visible’. If the problem has symptoms, and the symptoms are painful and getting worse, you have our attention. Symptoms that are stable or getting better feel much less urgent.

Painful–some problems have symptoms that aren’t so bad. And so we ignore them.

In our control–because helplessness is a feeling most people seek to avoid. The more certain the potential solution, the more likely it is people will acknowledge that there’s a problem.

Keep us from feeling stupid–because we don’t like feeling stupid, so we’d rather ignore the problem.

Status-driven–this one might be surprising. It turns out we like to focus our attention on things that will move us up the social hierarchy.

Expensive–problems that cost us money right now are ideal for this culture, because expensive = urgent.

Solvable–see that earlier riff about rationalization and chronic problems. If a problem doesn’t seem solvable, we’re a lot less likely to stake our attention on it.

Let’s take a look at how these each apply to fundraising appeals.

1. Visible

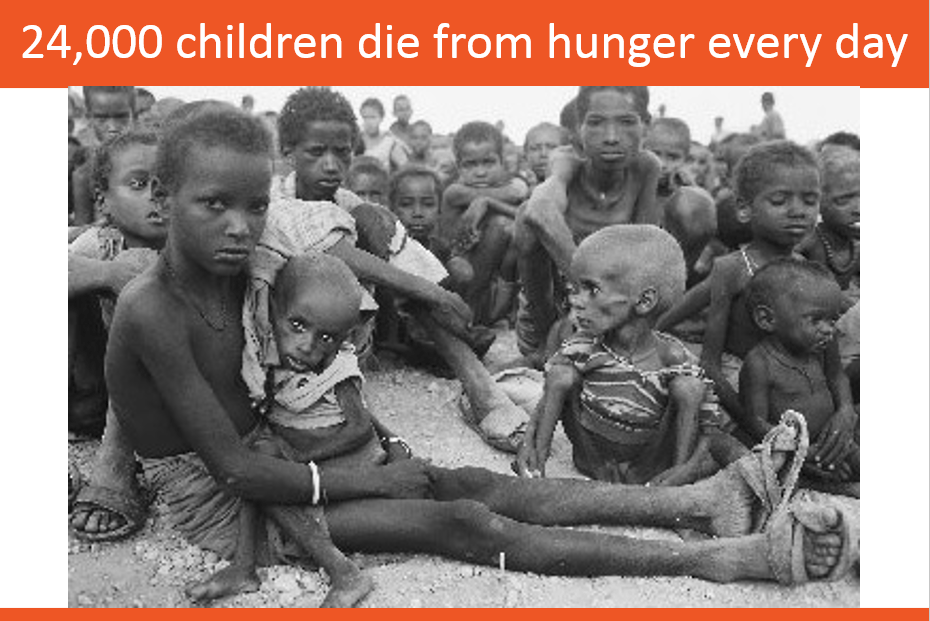

There’s a reason for the old adage “show and tell.” People believe what they can see. In fact, I used to define nonprofit “development” as being akin to developing a photo so compelling the donor would want to jump into it and become a part of the story. It used to be expensive to take good photos and make compelling videos; today, anyone with a smart phone can do it. Do it!

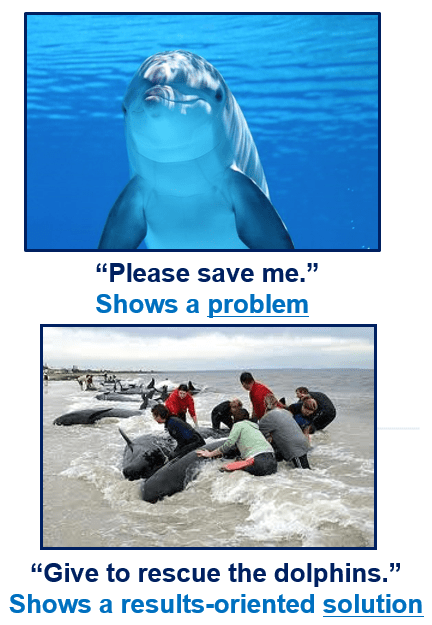

I like to find a photo before I even begin to write an appeal. If you can find a ‘story photo’ – one that pretty much tells your story without the need for narrative – you’re way ahead of the game. Just add a caption, and you’re good to go!

Here’s a favorite that shows the problem right away:

2. Non-chronic

2. Non-chronic

If a problem seems to have no solution it becomes daunting. What you need to avoid is your donor thinking “There’s nothing I can do about this. It’s just the way it is.” That’s a form of rationalization that will lead people to doing nothing. Because, what’s the point?

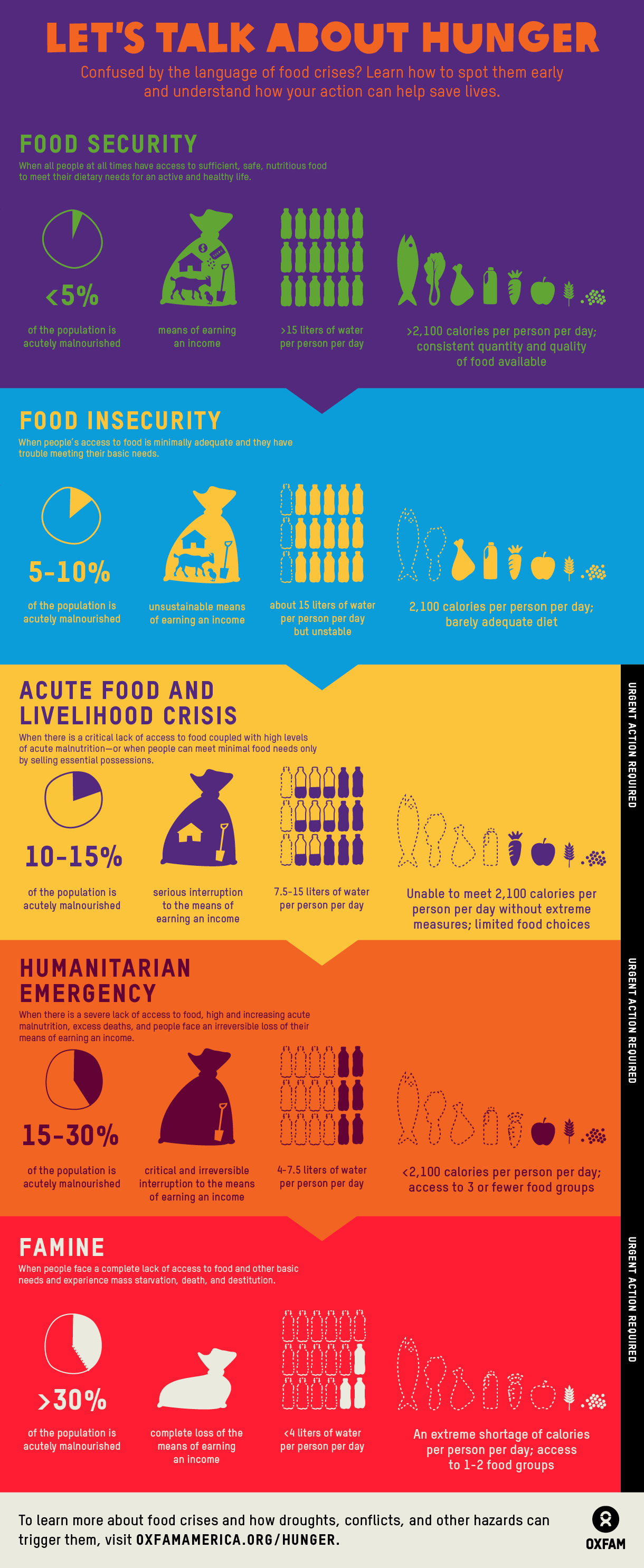

When you’re dealing with something like cancer, for example, you need to break the problem down into something approachable. Like cancer research, or therapeutic support, or palliative care. The same holds true for a problem like famine. Here’s how one organization, Oxfam, breaks it down.

3. Symptomatic

3. Symptomatic

Symptoms are evidence. In other words, they’re a way of making the problem visible. If you can demonstrate multiple symptoms this will increase the likelihood your problem will be perceived as believable.

Symptoms also bridge the gap between the present dismal situation, how this relates to a larger problem and how this problem can be resolved with the donor’s help.

4. Painful

If symptoms relate to a problem that isn’t perceived as painful, then… who cares? No one gets a lot of sympathy for a little sniffle. But if someone is clutching their mid-section, right where their appendix lies, that’s a completely different story.

You need to describe your problem in such a way that the would-be donor can feel the pain. One of the best ways to do this is to describe the problem in relatable ways. And the best way to do this is to tell a compelling, emotional story. For example, I may not have asthma, but when you tell a story about a Mom dealing with a little boy on vacation who was suddenly unable to breathe, and how she’s now able to relax and let her kid go outside in the summer, I can imagine what this might be like. I may not have a daughter with osteogenesisimperfecta, but as a parent I can relate to how painful this would be and feel enough empathy that it compels me to make a donation.

5. In our control

Suggest a believable, specific, results-oriented solution that relates directly to the problem. If there’s no controllable solution then would-be donors will conclude there’s no problem, just stasis. For example, if you tell me you’d like me to raise the ocean’s level by peeing in it, I’ll likely ignore you.

If birds are drowning in oil spills, show me how they can be rescued. If children don’t have access to clean water, show me how this can be remedied. If it’s local government policy not to offer arts in the public schools, show me what I can do to make a change.

Don’t feel compelled to expound on every nuance of what you do. Remember folks are interested in results, not process. They don’t so much care how you do it as that you do it. You may care you do this with 25 staff in four locations. Or that clients are helped “physically, spiritually, mentally and socially.” Your donor doesn’t think like you. S/he cares about the core problem your clients face, and what will enable them to overcome this problem. Donors give to the bottom line: the problem will go away – with their help.

Don’t feel compelled to expound on every nuance of what you do. Remember folks are interested in results, not process. They don’t so much care how you do it as that you do it. You may care you do this with 25 staff in four locations. Or that clients are helped “physically, spiritually, mentally and socially.” Your donor doesn’t think like you. S/he cares about the core problem your clients face, and what will enable them to overcome this problem. Donors give to the bottom line: the problem will go away – with their help.

Relate your solution to me by using the word ‘you.’ “Brenda and her kids will spend the night on the streets. Unless you help.”

Whatever you do, don’t ask me to give the gift of ‘hope.’ That’s not a specific solution, and it’s not controllable.

6. Keep us from feeling stupid

When you present a problem in a way it seems overwhelmingly huge, people may not want to touch it with a ten-foot pole. Because they must face their ignorance. No fun.

Complex problems can make folks feel stupid, because there’s so much to know and understand. A problem like climate change fits this bill. Often folks don’t allow it to penetrate their brain. They don’t even recycle religiously, because that would mean they’d have to confront the problem and really learn more about it.

The cure, again, is to break the problem into component parts.

The other cure is advocacy designed to get the problem to a tipping point where people will feel stupid if they ignore it. Godin notes this happened, over time, with cigarette smoking.

The other cure is advocacy designed to get the problem to a tipping point where people will feel stupid if they ignore it. Godin notes this happened, over time, with cigarette smoking.

7. Status-driven

Here the problem is that the donor is not perceived as positively as they could be. Sometimes when you attach your problem to a status-bearing solution you’ll attract folks who care about moving up the social hierarchy.

For example, everyone who gives at the Benefactor Level will receive name recognition on the donor wall. Or will be invited to a special reception where So-and-So-VIP will speak.

Don’t judge! There are many motivators for giving, and one is not better than another. They all drive philanthropy, and philanthropy drives mission.

8. Expensive

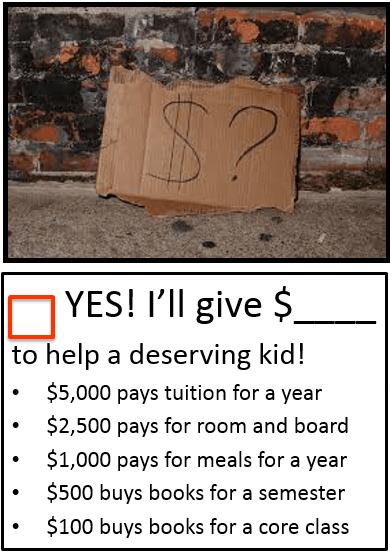

People like to move the needle; they don’t like to be a drop in the bucket. If the project costs a meaningful amount, the problem will seem meaningful. Accordingly, the donor’s gift will seem meaningful. Especially if you ask for a specific amount, and make it clear what that amount will accomplish.

Simply asking folks to “please give to the annual campaign” gives no indication of your goal or what the donor’s gift will accomplish. The same is true for the ubiquitous “a gift of any amount, no matter how small, will help.” It may seem polite and even inclusive, but it diminishes the importance of the giver.

9. Solvable

9. Solvable

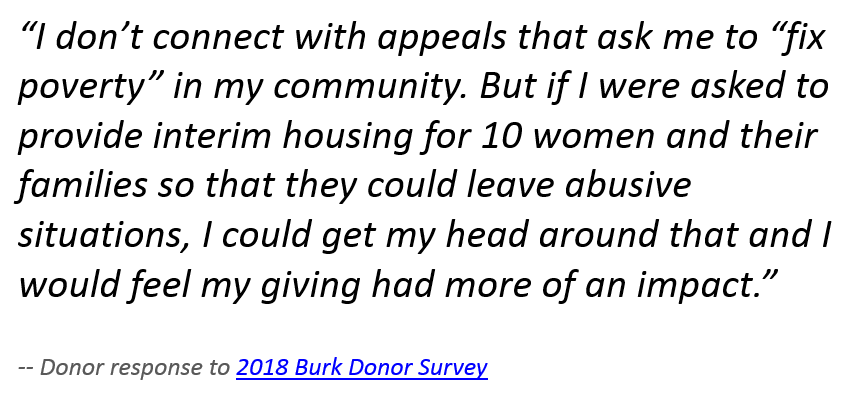

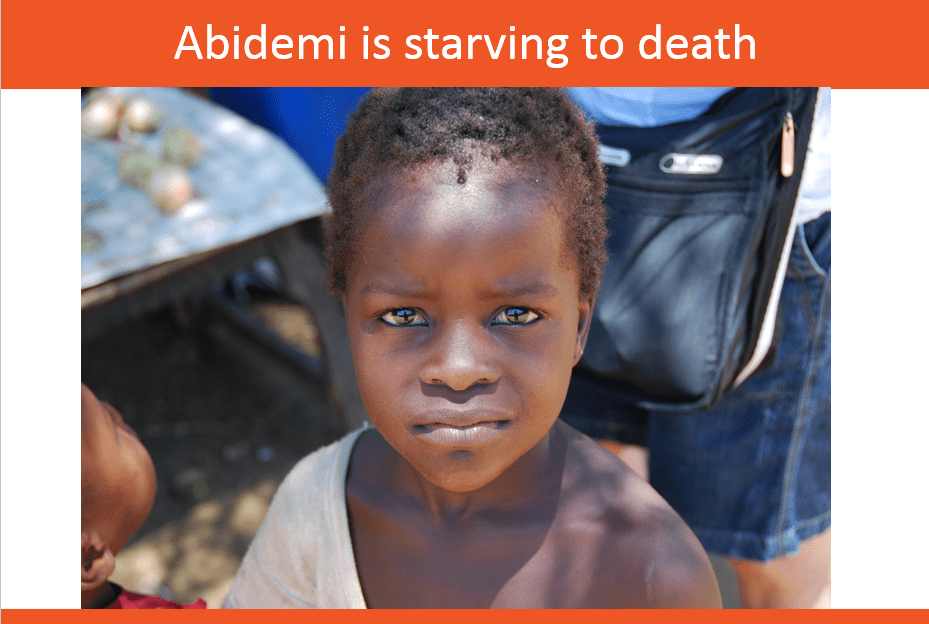

Connect the dots between the problem and the solution. Again, giant tasks are discouraging. The donor knows their one gift won’t fund all of your 20 different programs.

If the problem is too huge your would-be donor won’t be able to visualize making a difference. This is why telling an emotional story of one person, the “identifiable victim,” works better than talking about huge numbers of folks needing help.

See the difference between these two approaches. The first makes the problem seem too big to solve; the second is something people can wrap their brains around:

What have you found that helps the problem you address capture your donors’ attention? Please share in the comments below!

Want to Learn More?

This 62-page guide will take your appeal letter from run of the mill to out of the ballpark!

My Anatomy of a Fundraising Appeal Letter Plus Sample Template will help you create a compelling appeal your donor won’t be able to resist. It’s simple, step-by-step powerful stuff. If you follow these guidelines, you’ll raise more money. Period.

And if you’re not satisfied for any reason, I offer a 30-day no-questions-asked refund policy.